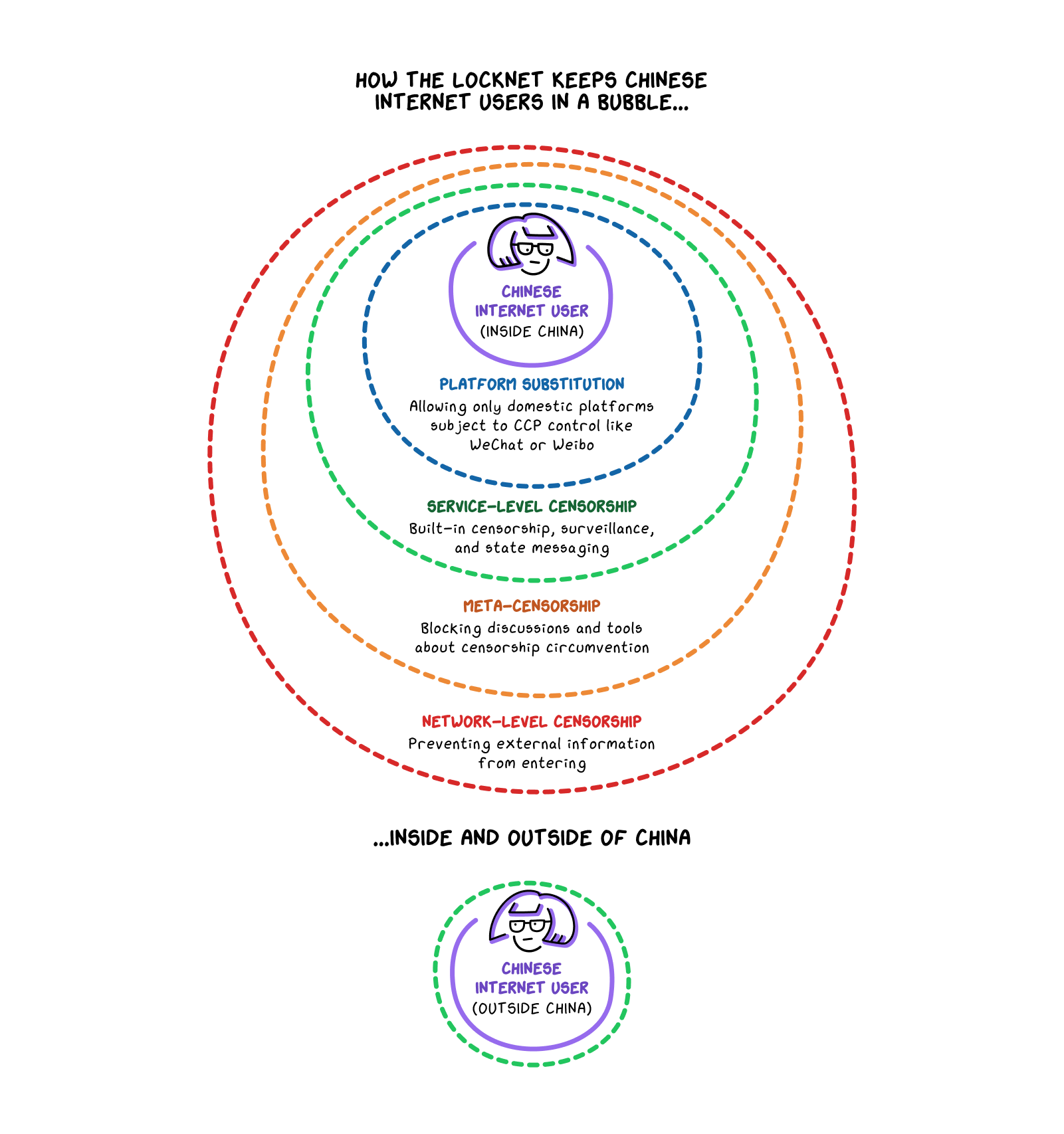

In general, the Locknet only targets communications taking place within or crossing over the country’s borders, removing “bad” or “dangerous” content from circulation. (This contrasts with Beijing’s propaganda efforts, which aim to inject content into both domestic and international discussions.) Even so, the effects of the censorship regime can and do ripple outwards into the broader world, because the Locknet was designed to be compatible with the global internet. Just as information from the outside can flow into China, systems built to control information can, and occasionally do, flow outwards. Often, this occurs when users outside China want to interact with services, users, or infrastructure inside China, forcing them to rely on the Locknet for tasks they would otherwise do on the internet.

Service-Level Censorship, Worldwide

Among the most obvious examples of this spillover effect involve international users experiencing content censorship on China-based or -designed platforms—essentially, externalized

service-level censorship

To avoid this problem, some companies offer separate versions of their apps for Chinese and international audiences, like ByteDance does with Douyin (the Chinese version) and TikTok (the international version). Theoretically, this means that CCP-imposed censorship stays on the Chinese version of the platform—but reality isn’t always that tidy. In 2019, an American teenager posted a video on TikTok, the “foreign” version of the Chinese app Douyin. Made to look like a milquetoast makeup tutorial, the video quickly shifts tone as the teenager decries the Chinese government’s treatment of Uyghur Muslims. TikTok removed the video and subsequently banned her from posting new content. Despite TikTok’s later claims that the video had been taken down in error, many observers concluded this was an attempt to silence international discussion of ethnic repression in China.

International users can also receive censored internet search results. Microsoft’s Bing has repeatedly declined to show certain search results and has also censored the autosuggestions it offers when users begin typing in the search bar. Though it’s unclear whether this behavior is intentional or simply the accidental result of China-tailored software exceeding its boundaries, even properly-functioning search queries can turn up censored results anywhere in the world. One academic study found that when users outside of China searched Google for images with Chinese-language terms, they ended up with censored results. “Google largely directs its Chinese language searches to mainland Chinese

IP addresses

AI chatbots developed in China also limit their responses to align with Party-state red lines, even if the user isn’t physically in the country. Several researchers have shown that such chatbots either provide standard CCP talking points or refuse to answer certain questions altogether. Even if users download and run chatbot software outside of China, where they are less likely to receive blatantly censored answers, the software might still default to the CCP’s standard propaganda playbook when formulating responses, like presenting the Party as the best source for accurate information, or treating any negative information about the Party as biased. And many users—including corporate ones, who incorporate Chinese chatbots into their own technology—don’t seem to care whether the chatbots are pro-CCP or not. In a recent test of Nvidia software that had integrated a version of Deepseek’s chatbot, the software produced answers that parroted “Chinese state framing just as it would appear in the country’s controlled media, particularly on sensitive topics like Taiwan … insist[ing] that the island’s ‘reunification’ with the PRC ‘is an unstoppable trend no force can prevent.’”

China’s

service-level censorship

China-based services do more than simply censor; they gather data about their users. Some of this data-gathering exactly mirrors what all modern social media platforms do, collecting information about users’ interests, emotional state, relationships, and patterns of behavior. The question for users is whether they want to provide that kind of personal information to companies in China, which must provide data to the Party-state upon request. (This concern informed part of the recent debate about banning TikTok in the U.S.) Other data-gathering directly serves to strengthen censorship back in the mainland. The University of Toronto’s CitizenLab, conducting research on WeChat, found in 2020 that “[d]ocuments and images transmitted entirely among non-China-registered accounts undergo content surveillance wherein these files are analyzed for content that is politically sensitive in China. Upon analysis, files deemed politically sensitive are used to invisibly train and build up WeChat’s Chinese political censorship system.”

Apps such as WeChat also function to keep Chinese citizens within the censorship bubble even when physically abroad, a “Chinese-language information silo” that many Chinese expats rely on for news even when other information is available to them. Essentially, they carry the censorship system with them in their pockets. The Party’s propaganda department did not create WeChat, but its widespread use among Chinese citizens living abroad must count among the department’s luckiest breaks.

Adapted from the testimony of Nat Kretchun, of the Open Technology Fund, in his testimony to the U.S. Congress Select Committee on the Strategic Competition between the United States and the Chinese Communist Party, July 23, 2024.

Just as they help keep Chinese citizens digitally inside China, Chinese apps can also help keep non-citizens out. As described by researchers at the Berlin-based think tank MERICS, real-name registration requirements for social media platforms—ranging from account verification from a Chinese phone number, government ID verification, to face-scans, to verification by other platform users—”have led to effective access barriers for foreign users” on some apps. Some Chinese apps are not even available for download abroad.

Network-Level Censorship, Outside China’s Networks

It’s not just apps spreading censorship abroad. The Locknet’s

network-level censorship

The same

DNS

International Self-Censorship

These examples all involve the Locknet’s leaking out into the wider world. But people fully outside of the Locknet can also make their own decisions that help spread the reach of China’s censorship.

For example, over the last dozen years or so, Google has chosen to comply with about half of China’s takedown requests for YouTube content. The Ministry of Public Security requested the removal of 412 videos, often about government corruption or top officials in China; Google removed more than 200 of them. Remember, the Locknet ensures that YouTube is not accessible in China, so all of these removals by definition affect content that is only available outside of China.

But decisions to self-censor don’t only affect large, influential corporations. In December 2024, a university in Tokyo discovered that someone had secretly embedded Tiananmen-related content on its website, meaning that anyone trying to access the site from China would get stopped by

network-level censorship

International Internet Standards: Efficiency at the Expense of Privacy

Despite all of the headaches that the uncensored global internet causes for China’s leaders, it still behooves Beijing to keep the Locknet connected to, and compatible with, the internet. To this end, it’s helpful if Chinese companies actively participate in international internet standards-setting bodies, which have been a guiding force in the internet’s evolution in the decades since their founding. “Internet standard-setting” isn’t a mere regulatory process, it can also be lucrative for companies whose standards are adopted as a global norm, giving commercial entities a financial interest in participating.)Yet standards developed in China may reflect the same values and norms that underpin the Locknet—for one, that users have no expectation of privacy from their government—and adoption of such standards could alter the global internet in ways that make it less free or that threaten users’ privacy.

Historically, the internet has had to manage a trade-off between efficiency on one side and privacy and security on the other. In its earliest days, the internet had virtually no privacy or security safeguards at all. Only after a number of large-scale internet outages in the early 2000s were such safeguards built in. Since then, networks have struggled with the tension between efficiency and privacy—with efficiency concerns usually winning out and privacy safeguards tacked on as possible. But for a government like China’s, which seeks to reduce the amount of information a citizen can conceal from the state, such a tension doesn’t exist at all. Engineers can dream up all the fantastically efficient mechanisms they want, without privacy concerns gumming up the works.

New IP

A case in point: an internet standards proposal for something called “New IP,” or, as a later iteration became known, “IPv6+.” The Chinese technology company Huawei first introduced New IP in an international internet standard-setting body in 2018. The proponents of New IP presented it as a means to address problems they foresaw for the internet in the coming years, mainly involving speed and dependability. As humans’ uses for the internet expanded and the need for near-instantaneous information transmission increased, they argued, citing “remote surgery” multiple times as a model use case, the internet’s existing mechanisms for routing traffic would simply not be adequately efficient or reliable. “Huawei framed it as a program for exploration,” says Antonia Hmaidi, Senior Analyst at MERICS, but in its essence New IP assumed that “the future of the internet should be based on a new type of infrastructure.”

Huawei was indeed correct that a proposal like New IP would improve efficiency and performance. Imagine, for example, that a major sporting event is being streamed online and everyone in a neighborhood full of super-fans is trying to watch it. Each fan’s phone, laptop, or TV individually sends requests to the broadcaster’s

server

Beyond streaming a big sporting event, there are lots of reasons a country or a company might wish to know more about the information its networks are transmitting. As Hmaidi explains, developing countries just building out their fledgling networks may wish to use a system like this to prioritize critical government services, like payments, over bandwidth-hogging services like Netflix. Or, an

ISP

Of course, a New IP-type network would also help censors avoid the time and expense of performing

deep packet inspection

Specifically, New IP proposed fundamental changes to the “network stack,” or the way in which different layers of internet architecture interact with each other. The current

network stack

New IP was never a fully-fleshed out protocol, but the proposal contained enough detail that it stirred up debate in the internet standards community. On one side, people raised concerns about surveillance, censorship, and whether or not New IP meant that China was now “openly advocating for others to follow its lead.” On the other, observers pointed out that New IP wasn’t fully baked and could still be altered; and that the existing U.S.-led internet order had failed on multiple fronts to protect users’ privacy, meaning that Western accusations of a Chinese plot to upend the internet were hypocritical, alarmist, and “borderline imperialist-racist.”

However, one does not need to divine the underlying motivation for New IP—nor believe the U.S. and other Western countries always act with blameless intent in the international sphere—to evaluate New IP at a technical level and assess its purported benefits and risks. A 2020 report by the internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (an international nonprofit that helps coordinate naming and address conventions across the internet) did just that, judging that New IP could threaten users’ privacy. The report questioned the need for New IP as a protocol, citing other protocols already in development throughout the standards community. It also cast doubt on the ultimate efficiency gains New IP would provide, given that the speed of light would continue to act as a brake on information transmission.

New New IP

As a brand name, “New IP” has died an unceremonious death. But aspects of the proposal are still floating around in standards bodies, often under the moniker “IPv6+.” (The plus symbol at the end of “IPv6+” is doing a lot of work here. IPv6, without the “+”, simply refers to an updated format for

IP addresses

Though not exactly the same as New IP, IPv6+ also discards layer independence and collapses the

network stack

Regardless of uptake in international standards bodies, Huawei has already begun using IPv6+ in its own networks. This means that Huawei-built networks around the world, such as those in Uganda, Rwanda, and South Africa, where the company has provided infrastructure at a low cost, will be employing IPv6+. As long as data stays wholly within those networks, it will be transmitted in IPv6+’s easier-to-surveil format.

No matter its branding, aim, or provenance, any technical specification that eliminates layer independence for the sake of efficiency has the same problem: it leaves internet communications more vulnerable to surveillance and censorship. This may not actually present a problem in some cases, like in a medical intranet that wants to support services like remote surgery but remains separate from the internet as a whole. And for nation-states like China, being able to more easily surveil its citizens’ communications is a feature, not a bug. For the rest of us, though, swiping right on our dating apps or texting memes mocking our government, we may not really want anyone else listening in. As the internet continues to evolve, we must ask: what is the ideal balance between privacy and efficiency, and what safeguards need to be in place to ensure that balance is maintained?