June 30, 2025

The man gazes earnestly into the camera, the glow from his computer monitor reflecting off his black-rimmed glasses. “This is more than just a cultural moment,” he says with a smile. “It’s something truly meaningful. This is about mutual respect, kindness, and efforts to understand each other. This feels so good!” he exclaims in a video he posted to RedNote, a China-based social media platform similar to Instagram.

It was January 14, 2025, and Zheng Yubin was speaking in English to American users who had recently surged onto the platform—more than half a million in just two days. Noting that the U.S. and China were sometimes viewed as rivals, he enthused that “today, through this connection, we are seeing something different, a more personal and human side. It’s not just about nations, it’s about individuals . . . people who share the same hope for more freedom and a bigger world. So once again, welcome!”

Over the following weeks, RedNote, also often referred to by its Chinese name of Xiaohongshu, played host to what appeared to be heartfelt exchange, as many Chinese users embraced the influx of Americans. Users from the two countries asked each other about their everyday lives, swapped cat photos, and even did homework together.

But something less joyful lay beneath all the good vibes. The Americans had joined RedNote as a way to protest the U.S. government’s incipient ban of a far more notorious social media platform, TikTok. Advocates for blocking the app argued TikTok’s wide reach, its wealth of information on each of its users, and the obligations of its parent company under Chinese law could allow China to use it to “[sow] discord and disinformation during a crisis.” American TikTokers, unconvinced, rebelled by downloading RedNote. “Our government is out of their mind if they think we are going to stand for this TikTok ban,” a U.S.-based user said in a video posted on RedNote. “We are just going to a new Chinese app and here we are.”

Whether or not Washington’s fears were well-founded, China’s government does indeed have the means to manipulate content on China-based platforms. As a Chinese company, RedNote must obey Beijing’s censorship dictates. Some newcomers realized this when their RedNote posts containing political speech got flagged for “violations” or when they found their accounts closed. In a group chat viewed tens of thousands of times, new RedNote users discussed how to avoid getting banned for posting taboo political content; other new arrivals said they would depoliticize their posts in order to “do as the Romans do.”

Meanwhile, RedNote itself scrambled to comply with its censorship duties. In January, China’s top internet regulator reportedly told RedNote to ensure U.S. users’ posts don’t appear in China-based users’ feeds. Some foreign users then reported sharp drops in views of their content; others complained that the app only showed them content posted by other foreign users. Through outsourcing companies, RedNote began recruiting English-speaking content moderators. As of May, the company was still looking for people to help review videos posted by foreign users.

This whole cycle—the proposed ban on one app with ties to China, Americans’ flocking to another, the brief window of cross-cultural connection, and finally censorship’s closure of that window—demonstrated both the fragility and adaptability of China’s system. New technology, or new facts on the ground, can quickly open up channels for freer discussion. Authorities, both government and corporate, can also quickly close them. The RedNote saga revealed the genuine desire for more day-to-day contact between average people in both countries, one that is threatened not by a ban on TikTok, which isn’t available in China, but by Beijing’s censorship regime itself. It also highlights how unprepared the outside world is to deal with China’s censorship system, even as it becomes more entangled with our online lives.

Most people know that China censors its internet. They’ve probably even heard of the “Great Firewall,” the clever moniker popularly used to describe that censorship. But despite its increasing impact on our online lives, most people outside China don’t understand how this information control system really works. What does it consist of? How effective is it? What is its ultimate purpose? And how much does it alter the internet in the rest of the world?

This study brings a rare interdisciplinary approach to these questions. We are a computer scientist at Northeastern University, and a researcher on China’s governance and society at ChinaFile. For more than a year, we worked as a team to interview experts, review decades’ worth of academic literature and media reporting, and track policy and implementation changes over time. We brought together insights from our respective fields with insights from linguistics and political science. Working across disciplines allowed us to break down subject matter silos to gain a broad view of the interplay between the technological and social aspects of China’s censorship regime. This yielded new insights about the system’s purpose, its capacity, and its likely trajectory in the years to come. It also allowed us to clear up longstanding misconceptions and establish new frameworks for future research. Because China’s online censorship regime affects not just people living in China but around the world, it’s more important than ever for all of us to better understand the system’s mechanics, efficacy, aims, and impact.

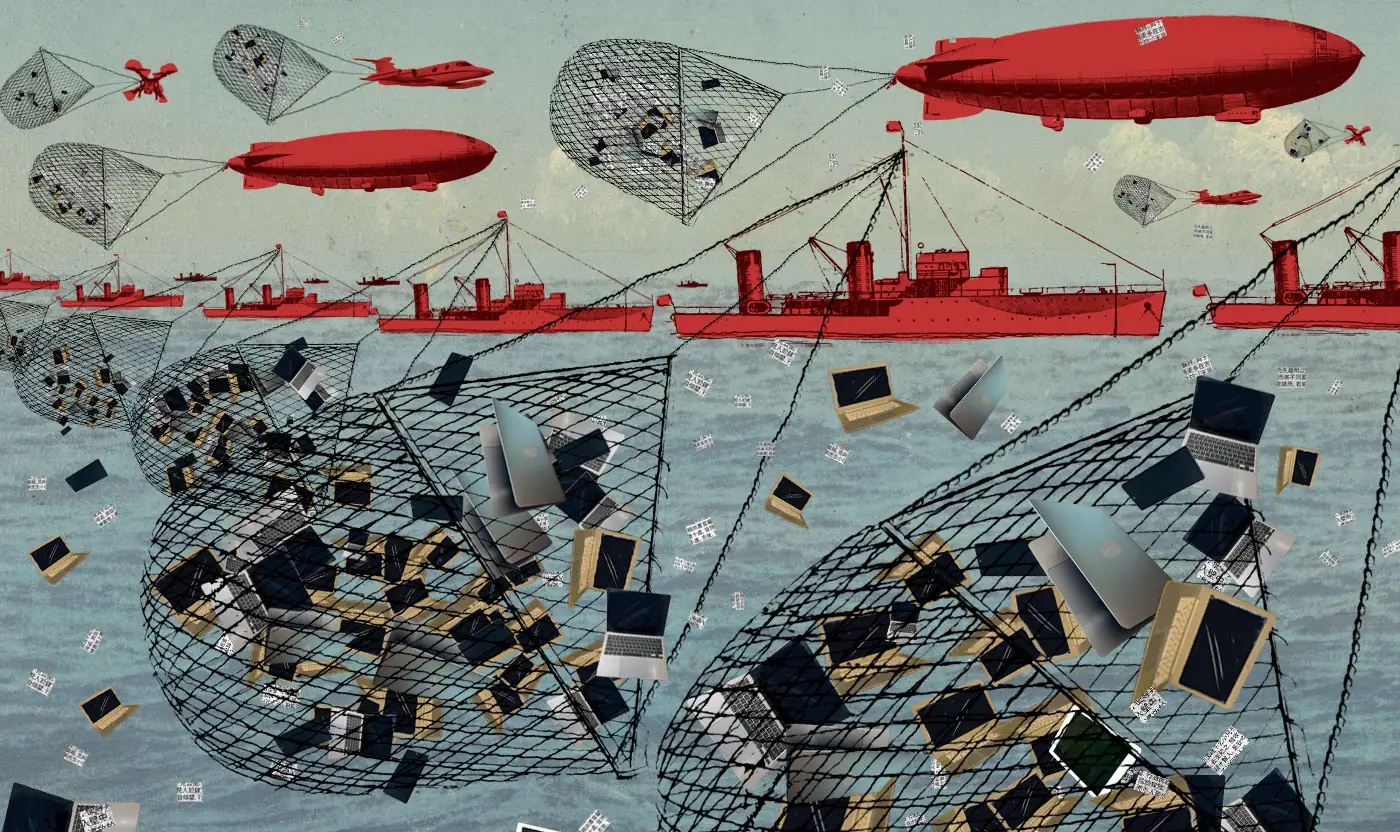

First, imagining China’s censorship system as a “wall” mistakes its true nature. The system isn’t static, it’s dynamic, multipart, and adaptable—and concerned with far more than simply repelling foreign information at the border. The system also embodies more than just a stack of servers and wires. It intertwines human and machine into a complex apparatus that pervades the online and offline worlds.

At the same time, the system is a resource-constrained, best-guess, partially-deployed patchwork, every component of which is imperfect and subject to failure at any time. Nevertheless, it remains highly effective and efficient. By not over-engineering this system, China built information control into its domestic internet in an economical way. In most cases, “good enough” censorship gets the job done.

Over the last decade, a number of influential scholarly works, widely referenced in media reporting, held that the main goal of China’s internet censorship was to forestall protests and other forms of collective action. But the country’s leaders have a much larger ambition: They seek to remake the broader information landscape such that it alters what citizens know, and even what they think.

Living in our digitally-connected world means that you almost certainly interact with this system, whether you want to or not. China’s online censorship apparatus increasingly shapes what appears on the global internet and the infrastructure that gets it there. We ignore it at our own peril.

For years, observers argued that Beijing would have to ease up on information controls in order to safeguard the country’s economic growth. Such a heavy hand, it was thought, would hinder innovation and productivity, eventually threatening the implicit bargain the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) had made with its citizenry: material prosperity in exchange for political submission. But this argument fundamentally misread the Party’s philosophy. China’s leaders view internet censorship, like a growing economy, as essential to good governance and to their continued rule—and they believe that such censorship becomes even more crucial when the economy slows and social discontent is on the rise. With this in mind, authorities have worked to forge a system that allows them to censor their internet without overly dampening economic growth. So far, they’ve been able to have their cake and eat it too.

Another common assumption held that China’s own people would slowly undermine the censorship system from the inside, engineering so many workarounds that it would eventually become too porous to function properly. But this assumed the system was beating back a tide of ardent “netizens” thirsting for unfiltered information. Yet, when was the last time you sought out foreign news in your second, or perhaps even third, language? In reality, most Chinese internet users appear to thirst after the same things all of us do: TV shows, sports scores, and cat videos, ideally in our native tongues. Even if it’s possible to evade the censorship system, the question is not just one of technical capability but of motivation. Often, just a little bit of friction, like a lack of circumvention tools for sale in the app store, or a slow or glitchy connection, is enough to convince people not to bother. After all, if Chinese users so fiercely desired the kinds of cross-cultural bonds that flourished briefly on RedNote, they might find ways to sign up for Instagram (banned in China) en masse. Instead, they largely stick to the services they can get from local app stores.

Of course, China’s online censorship system hasn’t withered away. Nor has its porousness doomed it to failure. The system remains indispensable to Beijing, and so Beijing has made sure it can grow and adapt in response to the internet itself.

And as the internet insinuates itself ever deeper into our lives, so does the chance it brings China’s censorship along with it.

More Than a Wall

Many countries censor the internet to some degree. By blocking specific content, or by limiting access to certain sites or services, states from Venezuela to Uzbekistan circumscribe what their citizens can see online. Some countries, such as Russia and Iran, have extensive filtering systems that allow their governments to monitor both content and the users who post it. North Korea simply doesn’t allow most people to get online at all.

But no other censorship regime rivals China’s in scale and complexity. Unlike Pyongyang, Beijing sees the value in letting its citizens visit cyberspace—and in fact continues to bank its governing and economic capacity on networked technologies. This means that China has, in some ways, a much more difficult row to hoe than North Korea. China needs the internet, but not all of the internet. It must find the means, across a large geographical area, and for more than one billion users wielding a wide array of commercially-produced computers, cell phones, and smart watches, to limit what information gets transmitted from one point to another.

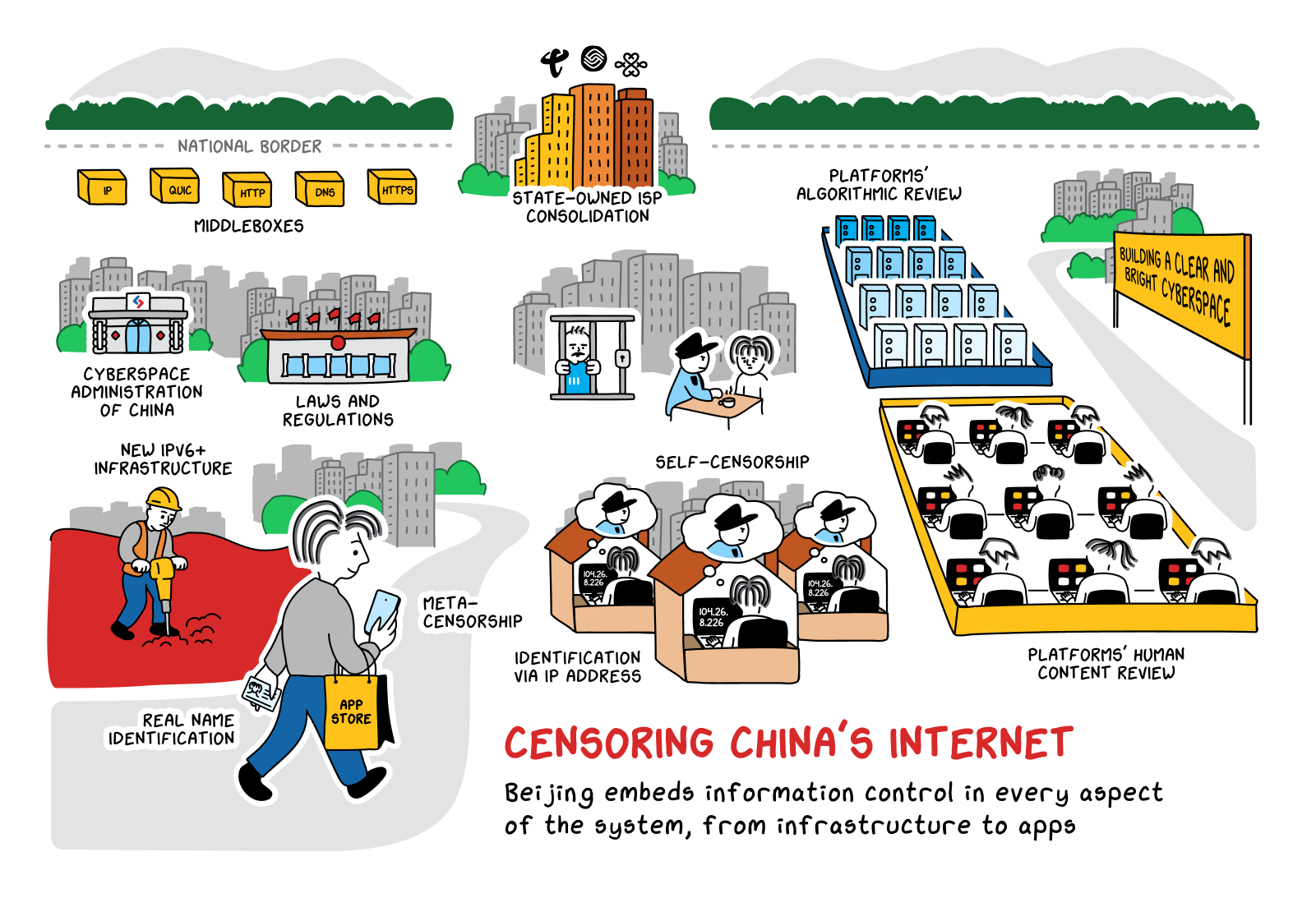

For most people outside China, the mention of Chinese censorship immediately brings to mind the moniker “Great Firewall.” As a metaphor, “Great Firewall” passably describes the digital fence Beijing has built along its borders. A barrier made up of hundreds, or perhaps thousands, of independent devices, it inspects internet traffic flowing in or out of the country—think of security guards manning border crossings—and disrupts connections it finds carrying objectionable content. In so doing, the Great Firewall conducts “network-level censorship”: monitoring internet traffic transiting the broader internet infrastructure, irrespective of who sent it, or from which platform. China’s network-level censorship tools, while individually rudimentary, work in tandem to create a system unrivaled in scope. They do so by violating underlying internet norms, like expectations of privacy and authenticity, to take advantage of the good faith and trust built into ordinary internet functions.

Even so, network-level censorship can only monitor information leaving or entering China. Internet traffic within China—a WeChat message sent from Guangzhou to Shanghai, say, or a video being streamed from Liaoning to Anhui—never comes into contact with the Great Firewall. But China seeks the option to censor any traffic that might reach its citizens, not just traffic originating abroad. This is where “service-level censorship” comes into play. Beijing has tasked “services” such as blogs, social media apps, and gaming platforms with conducting censorship on its behalf. This holds for any company hosting content in China, not just Chinese ones. Because most, if not all, such platforms have their own corporate content policies that they enforce through post deletion, account blocking, or upranking and downranking, they already have the means to enforce the government’s censorship mandates; a platform can just as easily delete a post that violates its advertising policies as one that calls for the downfall of the Party. The distinction between content moderation and censorship lies not in who does the deleting, but on whose orders the deleting is done.

And this is how RedNote found itself facing both a business bonanza and a political crisis at the same time. In almost any other context, a company would greet a large influx of new users as an unalloyed good. In China, such a breakthrough brings with it the possibility of danger: What if the new users can’t be adequately constrained?

Companies like RedNote don’t censor their users because they necessarily want to, but rather because it is a condition of operating in China. China explicitly requires companies hosting user-generated content to close, blacklist, and report to the government all accounts that “create and publish rumors, stir up hot societal topics . . . and transmit illegal or negative information, creating a vile impact.” Similarly, the government expects average users to “interact civilly and express themselves rationally.” Such rules cover just about any entity, human or corporate, that might post or host something online, giving the government a legal basis for removing content and penalizing offenders. An internet-specific bureaucracy, along with law enforcement and the justice system, ensures that punishments, when levied, have real bite.

These three filters—network-level censorship, service-level censorship, and regulation and enforcement—aim to purify what is circulating on China’s domestic internet. The latter two filters manage content produced within the physical confines of China’s borders, or within the digital confines of a China-based app, while the first filter, network-level censorship, handles content that authorities can’t stifle at the source. Together, they form a socio-technological apparatus that can reach into both the digital and real-world lives of Chinese citizens, if and when it so chooses.

A censorship system this large undoubtedly costs the Party-state a pretty penny in research and development, new hardware, and day-to-day upkeep—but no one knows exactly how much. In 2021, researcher Ryan Fedasiuk used available government budgets to estimate that “Chinese government and CCP offices engaged in internet censorship likely spent more than $6.6 billion (nominal USD) annually on related activities. Accounting for purchasing power parity, the number is likely closer to $13 billion.” This calculation is missing a large chunk of central government spending, which isn’t made public. It also doesn’t include the costs borne by private industry, meaning it’s likely a significant underestimate. The expense of this system stems from the assumptions baked into its design: any citizen could be up to no good, therefore the system’s substantial cost is proportional to the total population and not to the number of actual offenders.

The censorship system’s complexity belies the idea that it is merely a wall. The “Great Firewall” suggests an attempt at impermeability, a hard, static barrier running along the border keeping invading information at bay. But the metaphor fails to capture the scale and dynamism of the system as a whole. Beijing doesn’t just stand sentry over its digital borders, it monitors and censors information flows within the country as well. Moreover, the censorship system was never designed to be impermeable. Instead, it uses the most efficient means possible to minimize the quantity of “dangerous” information available to Chinese citizens online. Impermeability is expensive, and not all that much better, from a practical perspective, than simply filtering out the majority of unwanted content.

In practice, online censorship in China functions more like a massive water management system: an amalgamation of canals and locks that regulates what flows, through which particular channels, and at what times. It adjusts to natural rises and drops in volume, though it can be overwhelmed during a flood. Even when the sluices close, it’s not perfectly impermeable; ripples can always slosh over the edge. This can happen in both directions: a gush can surge in from the outside or what was meant to stay in can leak out.

Just as a system of locks and sluices surrounding a man-made lake can regulate the lake’s water level while tides or rivers flow in and out, so China’s online censorship system can ensure the information circulating through the country’s digital spillways mostly conforms to Beijing’s changing whims. The result is a national intranet that links up with the global internet but manages internal information flows according to its own rules. The result is what we have dubbed “the Locknet.”

Good Enough, Enough of the Time

The Locknet may be multifaceted and adaptable, but that doesn’t mean it’s always at the cutting edge of technology. Nor is it foolproof; a system contending with a population as large and as online as China’s will inevitably allow some unwelcome content to seep though. Still, the Locknet only needs to be good enough, enough of the time, for enough of the population, in order to be effective.

Take, for example, a

network-level censorship

The network-level censorship system isn’t even composed of a single set of unified hardware. Instead, censors have cobbled it together over the years with equipment from multiple different vendors. “We expected that censorship infrastructure in China was largely monolithic,” says Dave Levin, an associate professor of computer science at the University of Maryland, describing his mindset before a set of 2020 experiments. Instead, the results he and his fellow researchers saw made them realize the system is probably much more heterogeneous. “The most logical explanation, and our new mental model, is that it’s a lot of different boxes” with different operating systems and different flaws, “which likely means different manufacturers.”

Within this patchwork system, individual components sporadically fail. For instance, during busy times of day, too much internet traffic can flood the network-level censorship system and allow otherwise censorable traffic to slip through. Computer scientists have repeatedly found that somewhere between 3 and 25 percent of “sensitive” traffic somehow makes it past the system to its final destination, even without any effort to evade censorship. As one study put it, network-level censorship is “more a panopticon than a firewall, i.e., it need not block every illicit word, but only enough to promote self-censorship.”

Service-level censorship

Another relatively rudimentary service-level censorship method involves keeping specific apps off citizens’ phones entirely, through a practice known as “meta-censorship.” Many foreign apps—and sometimes even entire classes of apps, like Virtual Private Networks (VPNs), which allow users to access otherwise blocked foreign content—are not available from app stores in China. (For members of certain persecuted groups, like ethnic Uyghurs in northwestern China, having a banned app on your phone can lead to fines or even detention.) In turn, meta-censorship leads to “platform substitution,” whereby domestic Chinese users end up engaging mainly or exclusively with apps developed in China rather than those more widely available abroad. Greatfire.org, an organization that tracks online censorship in China, reports that in Apple’s app store, in particular,

66 apps (61%) out of the 108 most downloaded apps worldwide are unavailable to Chinese iOS users . . . none of [the top 10 most downloaded apps worldwide] are accessible to Chinese users. Five apps are simply not available in China’s App Store, while the remaining five, though available, are blocked by the government and cease to function once installed on a user’s device.

In 2023, Beijing codified its dominion over corporate app stores; regulations now require any mobile apps to get approval from the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology before they can appear in China’s app stores. Chinese companies have no choice but to work within these constraints. Foreign companies like Apple have opted to accept them in order to gain access to the Chinese market. Much of Beijing’s censorship power, therefore, derives simply from its role as a gatekeeper to one of the largest customer bases in the world.

Internet users themselves supplement network- and service-level censors. 22 Chinese internet users interviewed by researchers in 2024 all “reported practices of self‐censorship before posting online,” often simply opting not to post because “it is useless to speak.” The interviewees also “assert[ed] that they have a clear understanding of the ‘boundary’ between sensitive and insensitive topics, enabling them to navigate discussions online carefully” despite the fact that “none of them can clearly draw the line, nor do they draw the same line.” Similarly, a survey conducted in 2015 asked more than 2,000 respondents “whether they had ever changed the content of what they intended to write on a blog, Weibo post, WeChat message, forum post, or other online post so as to avoid being censored . . . nearly 25 percent indicated that they had done so several times and approaching 7 percent said they had done it many times.”

However, though many internet users in China clearly engage in some level of self-censorship, most people don’t go through their days thinking of ways to view or post banned material. One study gave Chinese university students access to the uncensored internet via a

VPN

Indeed, “people experience the Chinese internet in extremely varied ways,” says Daniela Stockmann, Professor of Digital Governance at the Hertie School in Berlin. “There are people who believe the internet is very censored, that they don’t have space to talk about hot topics or issues of social and political relevance. Other people think the internet is an incredibly diverse space. Of course, it depends on the topics you want to talk about and what platforms you’re on.”

But people’s experience of China’s cyberspace varies not just based on the content they’re seeking. Other factors also affect what they’re able to do online. Are you an elite academic or a businessperson whose work requires some additional access to international internet services? You may have access to a government-approved VPN that allows you to bypass some censorship. Are you trying to connect from Henan province, where authorities recently implemented their own, additional network-level censorship system? You may be subject to “dual-layer censorship,” with both the national-level system and the provincial-level one limiting what your computer can reach. “In Henan, specifically starting in 2023, people started noticing that there [were] hardly any websites they [could] access,” says Ali Zohaib, a Ph.D. student at the Security & Privacy Lab at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. Zohaib and his colleagues found that Henan’s

network-level censorship

No matter a user’s profession or location, no one is completely safe from crossing Beijing’s red lines. That’s because the red lines themselves aren’t static. Lists of forbidden topics can change, and certain groups of people can suddenly find themselves under mounting political scrutiny—as has happened to LGBTQ individuals and Hui Muslims over the past decade. Even members of such groups who strive to live within the bounds of the politically permissible may become politically impermissible simply by virtue of who they are.

The Locknet’s imperfections, and the vagaries of its implementation, can make it quite difficult to understand what the Chinese government is blocking at any given time. Is something blocked, or did it simply get dropped by overloaded equipment? If it is blocked, is it blocked for everyone, everywhere, or only for certain people, or in certain locations, in certain contexts, or on certain apps? Is the block intentional, or simply collateral damage from an unrelated content ban?

From the outside, the Locknet’s flaws can be hard to see. But failing to recognize these flaws can lead to inaccurate ideas about what content remains online. Let’s say a foreign website has cleverly disguised what authorities would deem “subversive” content and is still accessible in China. What does this tell us? That authorities have chosen not to block it? That someone within the censorship system secretly supports what it says and hopes to get the word out? Not necessarily. Such conclusions would be warranted if China conducted network-level censorship with what computer scientists call “allowlists,” only allowing access to pre-approved websites and services. But China’s system generally relies on blocklists, only blocking sites, services, and keywords already identified as problematic. (The sheer volume of problematic content can make it easy to forget that, in fact, much more content is not blocked at all.)

This means that “subversive” content might be accessible in China for a number of different reasons:

- First, yes, authorities may have chosen to allow it through. But this is only one possibility.

- Second, authorities may not know it exists, if it is indeed cleverly disguised or otherwise not caught by the automated dragnet. As yet, the censorship system can only block what it has been told to block. Novel formulations of “subversive” content won’t necessarily trigger any tripwires.

- Third, authorities may know about it but have judged it not important or dangerous enough to bother with. The system doesn’t need to be perfectly watertight, just good enough most of the time. There are likely plenty of cases, especially when considering the differing priorities of central and local authorities, when even “subversive” content just doesn’t rise to the threshold of concern.

- Fourth, authorities may want to block it but have decided that the cost of doing so is too high. This seems to be the case with the code-hosting website GitHub, popular with computer programmers and very useful to China’s burgeoning tech industry. Beijing initially blocked GitHub in 2013, but quickly backed down after public outcry. Since then, GitHub has been accessible in China only some of the time—clearly still a source of anxiety for authorities, but still too economically important to cut off completely.

- Finally, authorities may want to block the “subversive” content but do not yet have the capability. If the website in question uses new technology to serve up its content, China’s censorship system may not yet have developed a technical countermeasure.

In sum: internet content is available in China either because authorities like it, don’t know about it, don’t really care about it, don’t want to pay the cost to block it, or don’t have the means to block it. Notably, only two of these five possibilities represent a situation in which authorities have willingly allowed content to remain online. In the other three scenarios, they’re either unaware, incapable, or grudgingly accepting of its presence.

In the early days of the internet, it was easy to see gaps in technological capacity or enforcement as proof that savvy citizens could always evade the system—or even as reason to believe that some of the system’s gaps were intentional, a concession to public sentiment or economic reality. But this assumed that the censorship system’s goal was perfection: a pristine national intranet, populated only with pre-approved content. Instead, the system aims for adequacy, which is more than enough to achieve Beijing’s political ends.

By focusing on the system’s current failings, we miss the longer-term trajectory: the CCP generally achieves its internet censorship goals, whether it takes days or decades. The regime has the motivation, the patience, and the physical access to ensure that its dictates reign supreme in the end.

Just as in the casino, so it goes on China’s internet: eventually, the house always wins.

Making Thoughts Unthinkable

Beijing does not merely censor undesirable content. It also works to fill the void left behind by injecting or promoting favored content. Sometimes, the addition and subtraction of internet content takes place in the open. The government may announce it has suspended several platforms for lax censorship, or given out “positive energy” awards to the most “heart-warming or ideologically sound stories, photos, and people” appearing online.

In other cases, the processes of deletion and promotion are deliberately kept hidden. A user might search for facts about COVID-19 or the South China Sea, and receive bowdlerized search results, without knowing anything has been omitted. Similarly, that same user might find their social media feeds dominated by accounts that platforms have upranked at the government’s behest. This is known as covert censorship. Some American users of RedNote experienced such covert censorship when they discovered they were only able to see videos posted by other foreigners and not any from Chinese users.

China’s information control system increasingly relies on covert censorship, perhaps because, as political scientists Juha A. Vuori and Lauri Paltemaa explain, “in its ideal form, censorship is totally invisible, and is able to make thoughts unthinkable, not just uncommunicable. Here, censorship aims to affect the formation of discourses, not just their contents. For that to happen, the user must not be aware that the contents . . . are being censored.”

Vuori and Paltemaa have also shown that China’s censorship apparatus implicitly distinguishes between “dangerous” and “bad” information, something made apparent by how long certain terms remain blocked online. “The longer a word remains filtered, the more lasting danger it constitutes for the political system,” Vuori and Paltemaa write. “Dangerous” words, censored for at least one year, “either dealt with the ‘hard core’ of the political system and its functioning, or opposition to it.” “Dangerous” words included those that referenced topics such as the Politburo Standing Committee or national leadership succession. By contrast, merely “bad” words, blocked for shorter periods of time, presented only a temporary threat to the regime. The authors categorized these “bad” words as related to “Incidents, Scandals, Corruption, Crime/Misbehavior, Place Names, Disharmony/Unrest and Company.”

To the best of our knowledge, the Chinese government hasn’t proclaimed the “bad”/”dangerous” distinction anywhere; indeed, the more “dangerous” a topic, the less the government publicly discusses censorship of it. And yet, online platforms must still use this distinction, and other such implicit government direction, as a template for their

service-level censorship

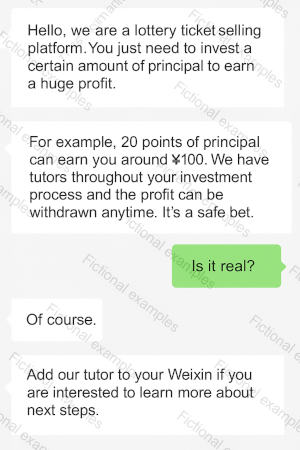

Like social media companies the world over, individual Chinese platforms publish their own content policies, designed to guide user behavior and offer clear boundaries the platform can use to police user-generated content. These content policies include both company-imposed rules (like forbidding competitors’ advertisements) as well as government decrees (such as forbidding pornography). They often include detailed examples of prohibited material. Yet, in abiding by the government’s unwritten rules, platforms can provide explicit examples only for relatively innocuous information. When proscribing more “dangerous” content, platforms tend to just repeat vague government jargon; to give more specific examples would be to mention the unmentionable.

Paradoxically, this makes corporate content policies an excellent guide to the topics China’s leaders most want to conceal. When a company describes a forbidden topic in generic or hazy language, that is often a sign authorities consider it “dangerous.” WeChat’s content rules, for example, offer up the following illustration of prohibited, but not “dangerous,” gambling-related content:

A screenshot from WeChat’s “Standards of Weixin Account Usage,” taken March 20, 2024.

By contrast, WeChat provides no explicit examples of what kind of content “damages national honor and interests” or “subverts state power.”

This ambiguity holds even when a user has already violated the rules. A respondent to a 2024 survey told researchers that, even though they had appealed to WeChat more than 20 times after finding their account blocked, they still couldn’t get any more information about their transgression: “They only tell you that you are breaking the rules, but they can’t tell you exactly what the rules are, or what I am posting that is breaking the rules.”

For certain types of “dangerous” information—like the Tiananmen Square massacre on June 4, 1989—Beijing doesn’t just remove content, but also seeks to “memory-hole” knowledge itself. Ideally, memory-holing eventually purges all traces of “incidents” such as June 4th from individual and collective consciousness. Of course, platforms still need their employees to know enough about memory-holed information to effectively delete it, creating a tension between the ultimate goals of censorship and the practical needs of implementation. Last year, an employee at a major Chinese internet platform described to an interviewer how the company handled this tension:

We’ve had training about evil cults, like Eastern Lightning [a banned spiritual group]. But it was just a PowerPoint presentation. No photos were permitted. As soon as it finished, the company quickly took everything away. All of the company’s training is secretive like that. My impression is that they need us to know about these things to do our job properly, but at the same time, they’re afraid of us knowing too much. They’d prefer we forget everything after executing their instructions.

This awkward tension between erasure and execution recurs throughout the system, affecting both man and machine. The platforms have a unique challenge: they must create actionable rules for their human employees and automated systems about topics that, from a political perspective, don’t exist. Their coders must know enough verboten information to properly program the platform’s content review algorithms, even if the government’s ultimate goal is that no one, not even the coders, know such information. Moreover, the platform’s users can never be explicitly warned against discussing “dangerous” information. Platforms have to tell their machines “no June 4th,” but they can’t tell their users “no June 4th.”

And this gets at the heart of the broader information control system: The goal is not just to limit what people see and say, but ultimately to limit what they know and believe. What many people think of as the system’s objectives—forestalling collective action, minimizing criticism of the government—are indeed present, but they only represent the system’s more tactical aims. The longer-term strategy is far more ambitious. To quell more distant threats, the Party hopes to cultivate an information landscape that won’t allow unwanted thoughts to grow.

Sloshing over the Edge

A censorship system as powerful and pervasive as China’s can’t be contained by a line on a map.

Network-level censorship

At the network level, technical tools designed to stop domestic users from reaching foreign websites can also affect users outside China. All it takes is for a foreign user’s internet traffic to transit China, however briefly. Because the internet’s traffic control systems assume all networks operate in good faith and by the same set of rules, they route traffic through China just like they would anywhere else, based on network congestion or availability. Of course, any traffic routed through China is subject to its network-level censorship—which means someone in Thailand could find themselves blocked from getting to the ChinaFile website (which is banned in China) if their traffic just so happens to cross the wrong border.

At the corporate level, any company hoping to make an online product that functions identically inside and outside of China will have to build Beijing’s censorship rules into that product. The wildly popular online video game Marvel Rivals, co-developed by the California-based Marvel Games and the Zhejiang-based NetEase Games, indeed follows these rules. The game doesn’t allow players to type phrases like “free Tibet,” “free Xinjiang,” “Uyghur camps,” or “Taiwan is a country” in the in-game chat, no matter where in the world the players log on. Marvel thus helped create an international product that has the effect of imposing Chinese censorship on global users. How many more companies will make, or are already making, a similar choice?

And, as Chinese companies assume a greater role in global standard-setting and infrastructure-building, Beijing’s ideas about basic internet norms and technologies are making their way into international discussions. The Chinese multinational Huawei has already deployed censorship-friendly technologies in places like Uganda, Rwanda, and South Africa. These technologies explicitly subvert long-standing expectations of user privacy in service of greater efficiency. The governments that control them won’t necessarily use them to surveil or censor their citizens, but the latent capacity is there. Global uptake of such technologies would reduce the ability for users around the world to safeguard their own freedom of expression.

China’s leaders treat speech, expression, and free access to information very differently from their counterparts in liberal democracies. These views, and the values that underlie them, shape the country’s laws and permeate China’s domestic internet infrastructure. In an increasingly digital world, that means their impact is global.

Americans’ behavior during the RedNote episode revealed how unprepared many of us are to deal with the Locknet. Though many TikTokers claimed the proposed ban would violate their First Amendment rights, a large number of the self-described “refugees” flooding RedNote hastened to sanitize their content to suit the Chinese government’s restrictions on speech. The irony of this self-censorship seemed lost on many of them, as did the true nature of censorship enforcement in China. One exiled activist wrote at the time, “The same complaint that brings you to RedNote have [sic] brought countless Chinese to jail. And the very app #RedNote you are using now is part of the state machine that white-washes the Uyghur, Tibet and Hong Kong issue, as well as silencing the entire voices of political prisoners, scholars, civil journalists, filmmakers, LGBTQ and feminists . . .”

Without a real understanding of what Chinese censorship is, those of us outside China could well end up enforcing it ourselves.

Additional reporting by Wenhao Ma.